Sections

Highlight

Fernando Alonso / Víctor Heredia

Malaga

Friday, 21 July 2023

On a hot afternoon in July, Alberto Palomo - archivist and sacristan of Malaga Cathedral- accompanied SUR to explain some of the secrets of the city’s main place of worship, secrets that are usually hidden from the visitor.

One of the most surprising security measures preserved in this, the principal church of the diocese, is the bar that secures the sacristy door from the inside. It is a long, square-shaped beam that is embedded into the thick side wall so that, when its full length (about three metres) is pulled across, it can be inserted into an existing hole on the other side. In this way, it fulfils its function of barring the door. This action was planned for exceptional circumstances and would allow the canons and support staff to take refuge in the sacristy and buy them some time to flee through a back door should the enemy enter this holy place. This defence mechanism reminds us more of the characteristics of a fortress when, in its early days, the cathedral was almost rubbing shoulders with the port wall.

The sacristy in Malaga’s cathedral is a marvellous treasure trove full of surprises. Among them is a small cabinet that Alberto shows us. It must be the most modern piece in the sacristy, because in it is stored a tiny barrel with the wine used for consecration at Eucharist (vinum missae). This wine is specifically called ‘lacrimae Christi’, or the tears of Christ, a native Malaga wine and with protected origin (Denominación de Origen). It has a very intense mahogany colour and is made from the must of grapes without mechanical pressing. It ages for a period of more than two years, without additives of any kind. The ‘lacrimae Christi de la Catedral’ is supplied by La Antigua Casa de Guardia winery, founded in 1840.

The cathedral has more than a hundred doors, each with its own key. In the sacristy they are gathered altogether in the one box. Many of them are made of iron and are large as they open very old doors. Every time Alberto shows us a new room, we have to go through the sacristy to change the key, since it would be impossible to carry them all because of their weight. It may seem surprising, but today the curious can find one of the keys to the cathedral of Malaga in a bar in Almeria. The reason is quite simple: during the first months of the Spanish Civil War, the church was occupied by many Republicans who took refuge in Malaga, fleeing from the Nationalist troops. Some of those refugees would end up taking this hundred-year-old key with them on their exodus to Almeria, popularly known in Malaga as ‘La Desbandá’..

Alberto leads us to an array of cubby holes and cupboards in the sacristy. This room was originally conceived as an antechamber to the real sacristy that is still yet to be built (another of the missing elements from the unfinished cathedral). Upon opening the doors of one of the large cupboards, we find ourselves facing a set of preserved relics.

There are about thirty in all, thirteen of which have certificates issued by the Holy See that guarantee their authenticity. Since the early days of the Church, Christians have venerated the relics of saints and martyrs and in this cabinet you can see some of special interest, such as that of San Flaviano, a Roman martyr from the 4th century; or San Luis, bishop of Tolosa, one of the patron saints of the city because his saint’s day coincided with the date of the reconquest by the Catholic Monarchs; a Lignum Crucis (fragment of the Cross of Christ) and a piece of the veil of the Virgin Mary. One relic of special artistic value is that of the arm of San Sebastián, which comes from the old Jesuit College, made of silver and dating from the year 1600. A Latin inscription carved into the wood of another of the sacristy’s cupboards reminds us of the value that has always been attached to relics: “The bones of saints drive away demons and make them tremble in fear.”

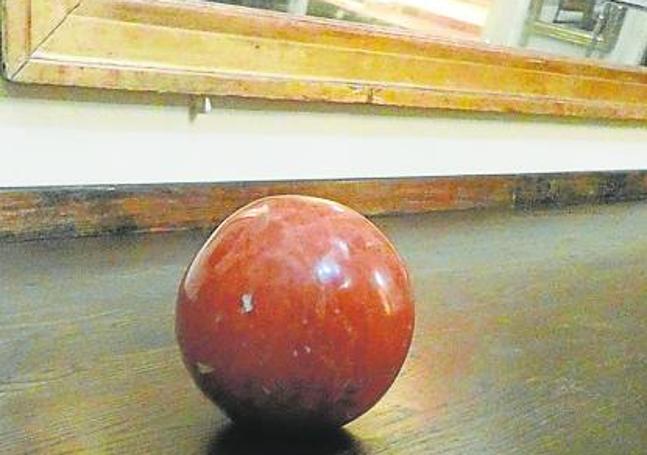

Malaga's main basilica was also residence for a long time to the various staff who looked after the place: bell ringers, organists, sacristans, workmen and even a canon. These people lived in the main towers and in the two small defence turrets (cubillos), in suites with artistic, baroque balconies, with spectacular views of the city. Round, stone balls, the size of bowling balls, finished off the ends of these balconies. They were removable and only one remains.

This beautiful ornament was removed to put glass lanterns in its place. They were known as bombas for their round shape, and were used as wax and later gas lamps. They were only placed on the balconies and other decorative points around the cathedral on important occasions: Queen Isabel II’s visit to Malaga, the birth of a new royal prince or any other exceptional event to celebrate. There were hundreds of them, so setting them up and lighting them must have been hard work.

Over the centuries, the people who have visited the cathedral have usually succumbed to the temptation to leave a ‘souvenir’ of their presence in the form of painted or engraved grafitti on the walls of less frequented places, such as the interior of a tower or the rooms inside the cubillos. It must not be forgotten that these spaces were inhabited, or were used for surveillance purposes at some point. The grafitti usually comprises names and dates, although sometimes there are drawings of architectural elements, the portrait of a bullfighter or, surprisingly, the silhouette of a warship from the early 20th century. Due to its location, being on the side closest to Malaga’s Parque gardens and the port, perhaps whoever sketched it had the ship in sight when they did so.

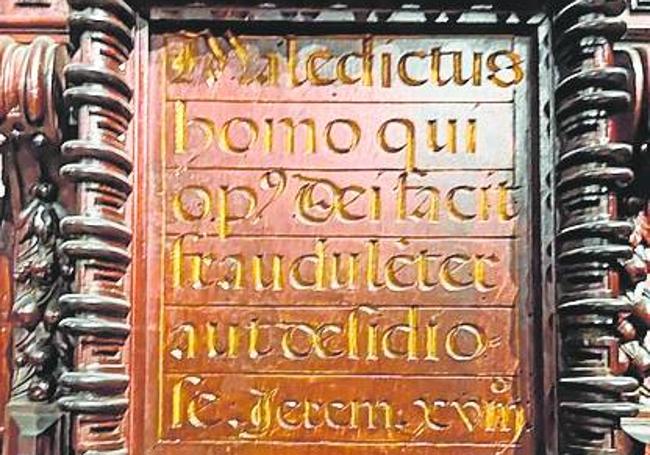

The choir stall of the cathedral is considered one of the best in Spain, along with those of Toledo and Cordoba. The canons and prebendaries of the cathedral used to spend a lot of time each day praying the canonical hours. Under their seats were the so-called misericordias, supports designed to rest lightly on, so that the priest appeared to be standing upright. But, despite this support, it was not unusual for someone to allow himself to fall asleep. For this reason, on the main wall of the choir stalls you can see a square placard with a stern warning containing a verse from the prophet Jeremiah which, translated from Latin, reads: “Cursed is he who does God’s work with slackness.”

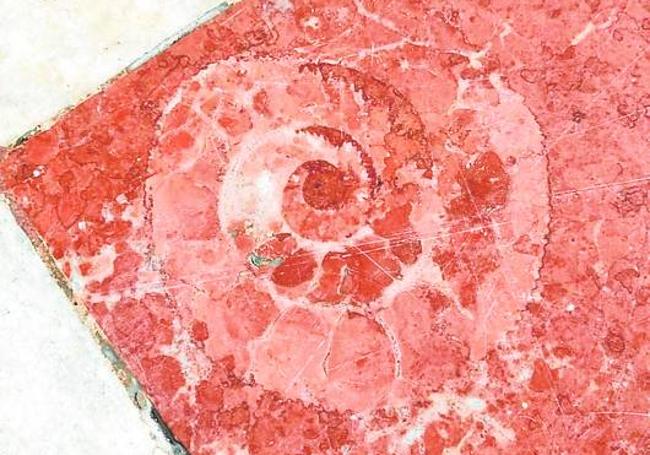

On approaching the exit, our host encourages us to look for the outline of an ancient fossil on the flooring. After looking carefully between the white and reddish stone slabs closest to the Puerta de las Cadenas (Gate of Chains), we could make out the unmistakable profile of an ammonite, a mollusc that existed millions of years ago and that remained fossilised in a rock from which, much later, the stone for the floor of the cathedral was extracted from a quarry in El Torcal, in nearby Antequera. The restoration of the floor, carried out by the Molina Lario masonry school in the 1990s, helped to bring to light several of these fossils, which today constitute another attraction for Malaga’s principal place of worship.

The walls, doors and furnishings of the cathedral are home to a numerous and varied fauna that represent real and fantastic beings and that hold a symbolism that sometimes eludes us.

These representations, made of different materials and from different periods, are distributed throughout the church: in the choir, on the altarpieces, in the pulpits and on the doors.

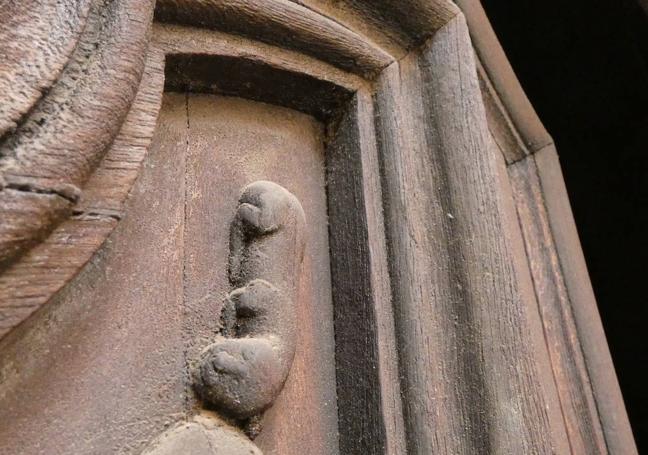

Our guide this afternoon leads us to the Puerta del Sol, the doorway of the transept facing Calle Postigo de los Abades , which historically has had less use. Like its twin, the Puerta de las Cadenas, the magnificent wooden leaves that close are carved with reliefs depicting the scene of the Incarnation, the Archangel Saint Gabriel and the Virgin Mary. There are also carved motifs taken from the Litany of the Virgin, but the most difficult to observe and which Alberto points out to us are two small animal figures. One looks like the head of a weasel or a ferret and the other shows the curled-up body of a feline, probably a cat. In medieval bestiaries the presence of these creatures is usually associated with negative signs, although we do not know the true intention of the craftsmen who assembled these magnificent doors.

-kxKB--650x455@Diario%20Sur.jpg)

In the cathedral of Malaga are stored a pair of caligas or episcopal slippers, which the bishop wore when officiating at holy ceremonies. Putting on these garments was carried out in full view of the faithful, as is still the custom in Eastern churches.

These unique shoes were richly embroidered and stitched with gold thread. Each bishop had his own caligas, for obvious reasons of size, and they had different colours according to the corresponding holy season.

Previously, the bishop would have also donned purple gaiters or stockings (polainas) bearing the episcopal coat of arms embroidered with silk thread.

A shoehorn was used to put on the caligas. A copper one is preserved in the cathedral.

The gloves that the bishop wore on special occasions, such as processions or blessings, are also kept in the cathedral. All these garments were part of the holy wardrobe.

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad

Esta funcionalidad es exclusiva para registrados.

Reporta un error en esta noticia

Debido a un error no hemos podido dar de alta tu suscripción.

Por favor, ponte en contacto con Atención al Cliente.

¡Bienvenido a SURINENGLISH!

Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente, pero ya tenías otra suscripción activa en SURINENGLISH.

Déjanos tus datos y nos pondremos en contacto contigo para analizar tu caso

¡Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente!

La compra se ha asociado al siguiente email

Comentar es una ventaja exclusiva para registrados

¿Ya eres registrado?

Inicia sesiónNecesitas ser suscriptor para poder votar.