Sections

Highlight

Regina Sotorrío

MALAGA.

Friday, 17 May 2024

José Manuel Benítez grew up in Miraflores de los Ángeles, a working-class neighbourhood of Malaga city, in the 80s and 90s, the son of Ángela and Manuel, a cleaner and taxi driver.

He was his parents' pride and joy: a responsible child and a good student, with everything in his favour to become the first in his family to graduate from university. Medicine was an option.

"For my mother this was top; it was what she had wanted and was never able to do."

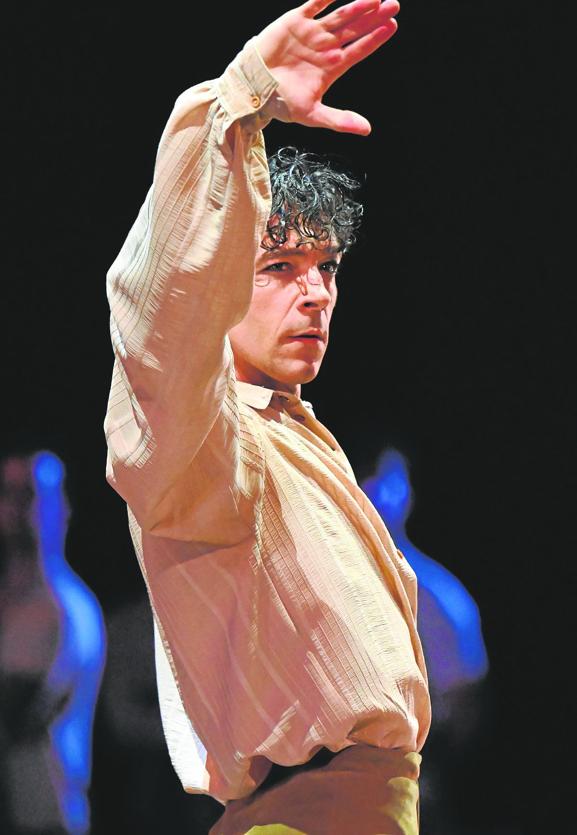

But then dance crossed his path. When his parents saw him move around the stage of a big theatre in Madrid, they understood. He had not made a mistake: from that studious child raised in a humble family, today he is a principal dancer at the Ballet Nacional de España (BNE).

For this interview, José Manuel Benítez answers the phone after a day of rehearsal and practice. He has officially been the company's principal dancer for four years - 19 have passed since he joined the corps de ballet. And he soon turns 43. "Your body hurts, yes. You no longer have the energy of a 20-year-old, but age gives you serenity and that is also marvellous," he points out.

This Malaga-born ballet dancer is one of the faces of the provincial tourist board's latest campaign, Grita Mi Nombre (Shout My Name), created by the Malaga agencies Narita and Dispar, and just one year ago he accompanied dancer Sergio Bernal in his performance at Malaga's Teatro del Soho CaixaBank. But he spends nearly all of his time at the Ballet Nacional, the flagship of Spanish dance; this is the goal that many aspire to but few achieve.

He says that as a child he never thought of devoting himself to dance. Encouraged by a friend, he took it up as an extracurricular activity at his school in Miraflores de los Ángeles, but he did not know that he would be able to live off it.

"For me it was a way to escape; I was always very responsible with my studies," he explains.

He was good at it, so he began passing the different levels of formal training. He received his Master's in Performing Arts, followed by a Diploma of Higher Education in Dance, after which he attended the Conservatorio Profesional de Danza in Malaga. During this time he auditioned for a flamenco training workshop organised by the then Compañía Andaluz de Danza, now called the Ballet Flamenco de Andalucía. And he got in. He then moved to Seville to continue his training.

"It was one of the best experiences of my life. It turned out to be eye-opening. I realised that, as the most responsible person in the world, I had stopped studying; dance was taking up more and more of my time." There was no going back; he made the jump to the main company, in the hands of choreographer José Antonio Ruiz, and began his career as a professional.

He says that in order to go far in dance you have to work a lot and "love what you do; it is totally vocational". But luck is also a factor. "Many talented people haven't had the opportunities because they weren't in the right place at the right time."

But he was. His evolution was partly due to the choreographer from Madrid who opened up doors for him in the dance world. Leaving aside Andalusian ballet, his next project was accompanied by Ruiz, whom he followed to Madrid shortly after, when he was appointed director of the Ballet Nacional de España.

José Manuel Benítez had to wait one year until he could audition for the company's corps de ballet; a time when he earned a living as best he could.

"I was broke when I came to Madrid and filled up my time with work." He sold soap, served drinks in a pub and danced with Paco Mora. But he also experienced unique moments, such as the filming of Carlos Saura's Iberia, his collaboration with the Rome Opera Ballet School, as well as a whole summer spent tapping his feet in Granada with flamenco dancer Mario Maya. "While I was there the auditions came out for the ballet, and I got in."

He knows that he is fortunate, but so that no one is mistaken: "We don't live like kings."

Now his contract is indefinite, but for over ten years he was bound to temporary ones. "You always live with uncertainty. You don't know when you're going to be able to work or if you're going to get knocked back. It's a short career and it's not paid enough, considering its duration," he says. He clarifies that it is not the BNE's problem, but rather that of how Spain's general culture values the sport: "dance is that black sheep".

He still has "a few years" left on stage, but he knows that this time will come to an end. "And it's very difficult to move away from that. Your professional life doesn't give you time to prepare for the day that you stop dancing."

For these professions there are no plans for early retirement, nor is there any plan to help them integrate into other types of employment. This is the current challenge, where they are trying to establish a process within the National Institute of Performing Arts and Music (INAEM) for those who step down from the stage but are still at working age.

While he can, José Manuel Benítez will keep dancing, contorting his body and giving his all in every performance, without missing a step.

Before stepping onto the stage, he looks for his grandmother in the crowd and visualises his mother - who passed away ten years ago - somewhere in the stalls. "They still help me."

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad

Esta funcionalidad es exclusiva para registrados.

Reporta un error en esta noticia

Debido a un error no hemos podido dar de alta tu suscripción.

Por favor, ponte en contacto con Atención al Cliente.

¡Bienvenido a SURINENGLISH!

Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente, pero ya tenías otra suscripción activa en SURINENGLISH.

Déjanos tus datos y nos pondremos en contacto contigo para analizar tu caso

¡Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente!

La compra se ha asociado al siguiente email

Comentar es una ventaja exclusiva para registrados

¿Ya eres registrado?

Inicia sesiónNecesitas ser suscriptor para poder votar.