Papers from Napoleon’s invasion of Malaga turn up at a Costa del Sol flea market

The Duke of Dalmatia and Marshal Sebastiani led the bloody assault on the city in 1810, which was also fined twelve million reales for resisting. The documents found at Benalmádena’s flea market bears both their signatures

It started at the point where today Avenida Lope de Vega meets Plaza de Manos Unidas in Teatinos. At that time the area did not bear those names, nor did it look like it does now. The road led to Malaga, as it does today, but back then this was just a dusty track beyond the suburbs. On that winter’s day, the atmosphere was chilly. Still, blood was running hot, not cold, as the city, far from surrendering to the Napoleonic troops as its leaders had originally agreed, raised its first line of defence here.

There were soldiers, but women and children too, who armed themselves with whatever they had to hand to confront the invader.

Malaga’s version of Madrid’s famous 2 May uprising was 5 February 1810 when the city fell, many slaughtered by blade and bayonet. This was no small punishment for such disobedience, nor the only one. Marshal Horace Sebastiani de la Porta, commanding the IV Corps of the Grande Armée and the Polish Lancers, ransacked the city and fined it 12 million reales (the Spanish currency at the time) for resisting.

Now the manuscripts of that bloody episode of this invasion by the French have turned up more than two centuries later in Benalmádena’s flea market.

“When I saw the documents I knew they had value, but my surprise was when I studied the texts and saw that they were signed by Napoleon’s marshals in Spain, who led the conquest of Malaga,” says José Antonio Fernández Molina, an antiquities appraiser and “someone who recovers lost history”, a definition he prefers to that of collector.

The specialist speaks with authority, as he is also an accredited legal handwriting expert. So, with this mixture of passion for history and a professional search for truth and accuracy, he certifies the authenticity of the documents. This is local history, so close to home that the events took place just behind where Fernández poses for photographs, in front of the commemorative plaque and the park dedicated to the Héroes del Combate de Teatinos, remembering those heroic, dark moments when the French invaded Malaga.

The collection of 14 documents was acquired only a few kilometres from here, at the Wednesday flea market in Benalmádena, apparently from a house clearance undertaken by one of the traders. Just like in those TV programmes featuring abandoned storage containers with traders bidding blind on their contents in the hope of finding something of value inside a piece of furniture or packing crate. In this case, the unexpected treasure was some old-looking papers that have turned out to be part of Malaga’s epic history.

The fine to Malaga for showing resistance

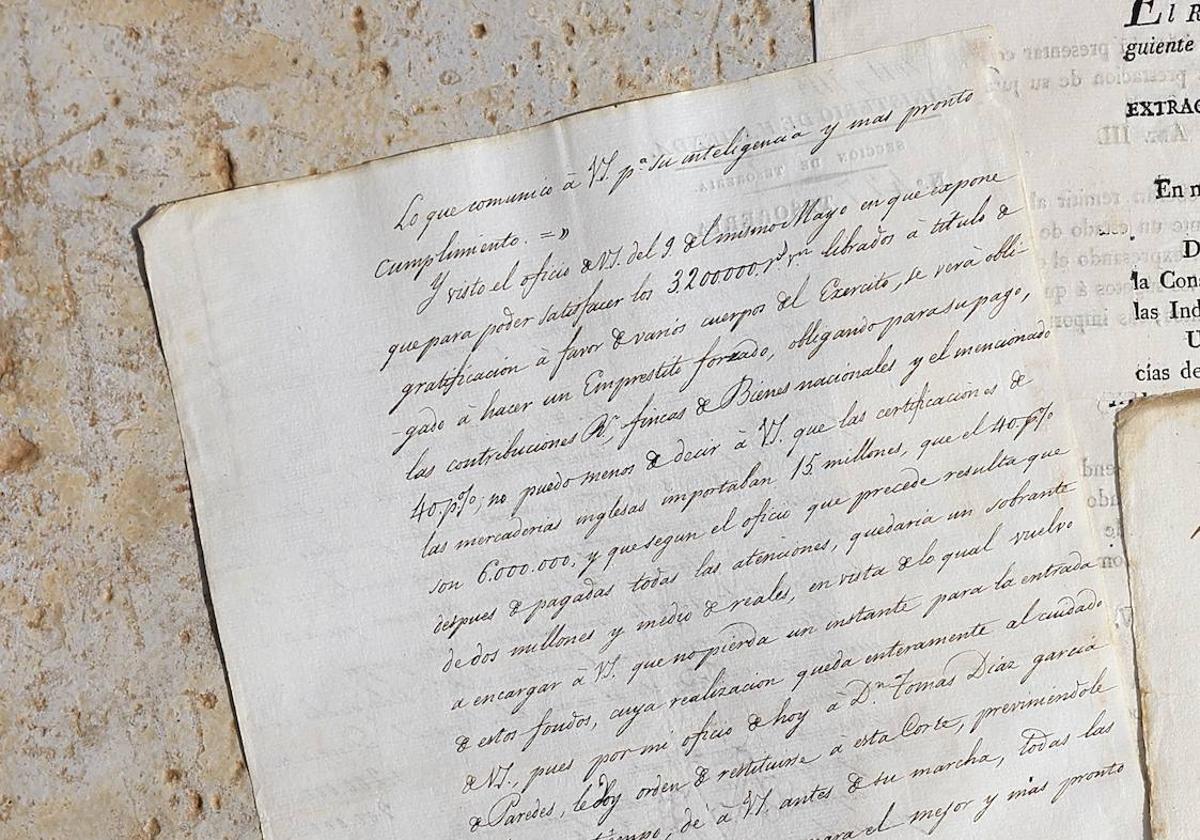

The most valuable document in the collection is signed by General Sebastiani in 1810 and demands, in nice words with veiled threats, the payment of 12 million reales from the city after it fell to the French troops. Ñito Salas

Napoleon's right hand man in Spain.

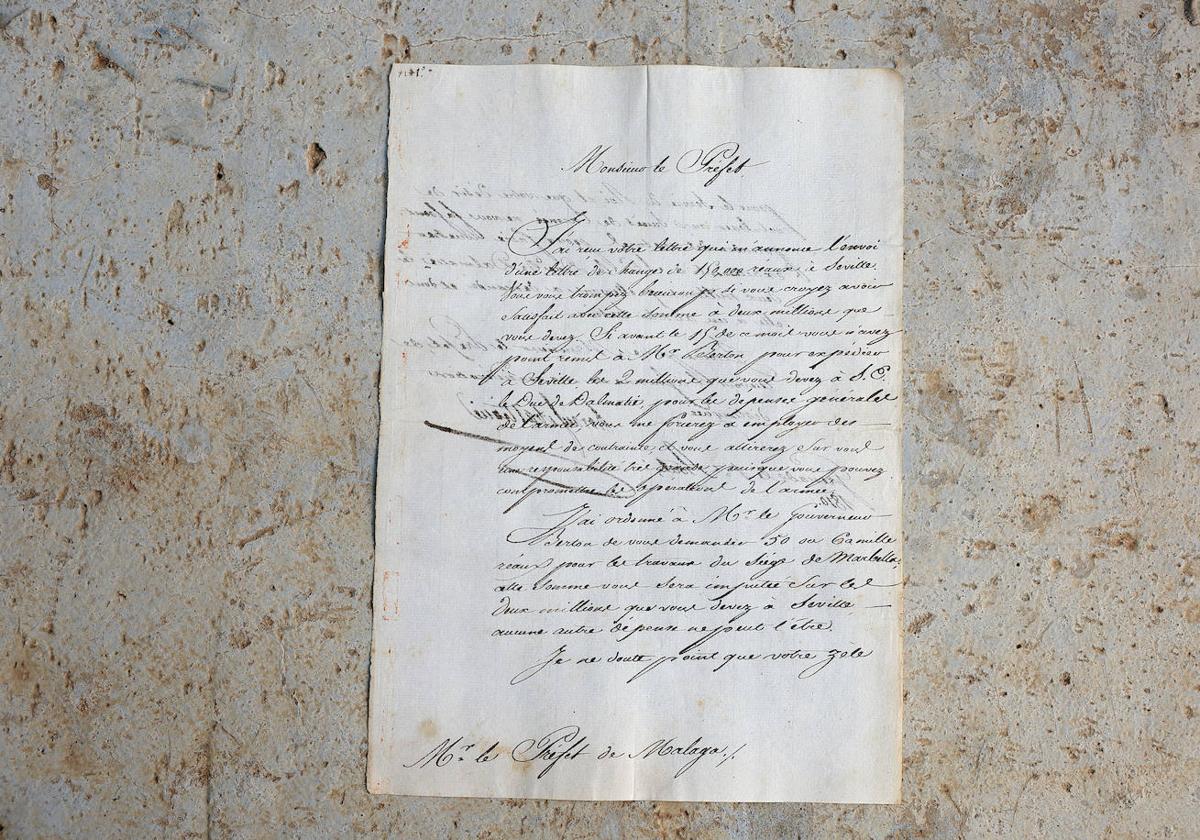

This letter from the Duke of Dalmatia, who fought alongside Napoleon in Austerlitz, shows his harsh side as he reprimands the prefect of Antequera. Ñito Salas1 / 2

How did these official documents come to be in a collection on the Costa del Sol? “We don’t know; after two centuries there have been many ups and downs in life, items moved around and fires which, even when they don’t destroy the archives storing this type of records, can still cause them to be dispersed,” explains this expert with a canny eye for finding treasure amid the trash. Some of his finds include the helmet of second world war aviation hero John Braham, the original plans for the remodelling of the walls of the Alhambra from the 19th century and the memoirs of a German Jewish musician, a relative of Albert Einstein, who narrated the Nazi hell lived through in the first person.

“I believe that the objects come to me; I say this humbly, but it is true that I have a special magnet for finding these pieces.” He enjoys telling of his experiences, debuting as a writer less than a year ago with the novel El Tasador de Antigüedades ( The Antiques Appraiser), a thriller set in the world of ancient art that he knows so well. He is already putting the finishing touches to its sequel, La Corona de Espinas (The Crown of Thorns). “I hope to publish it at the end of 2024 or the year after,” he says.

The most valuable

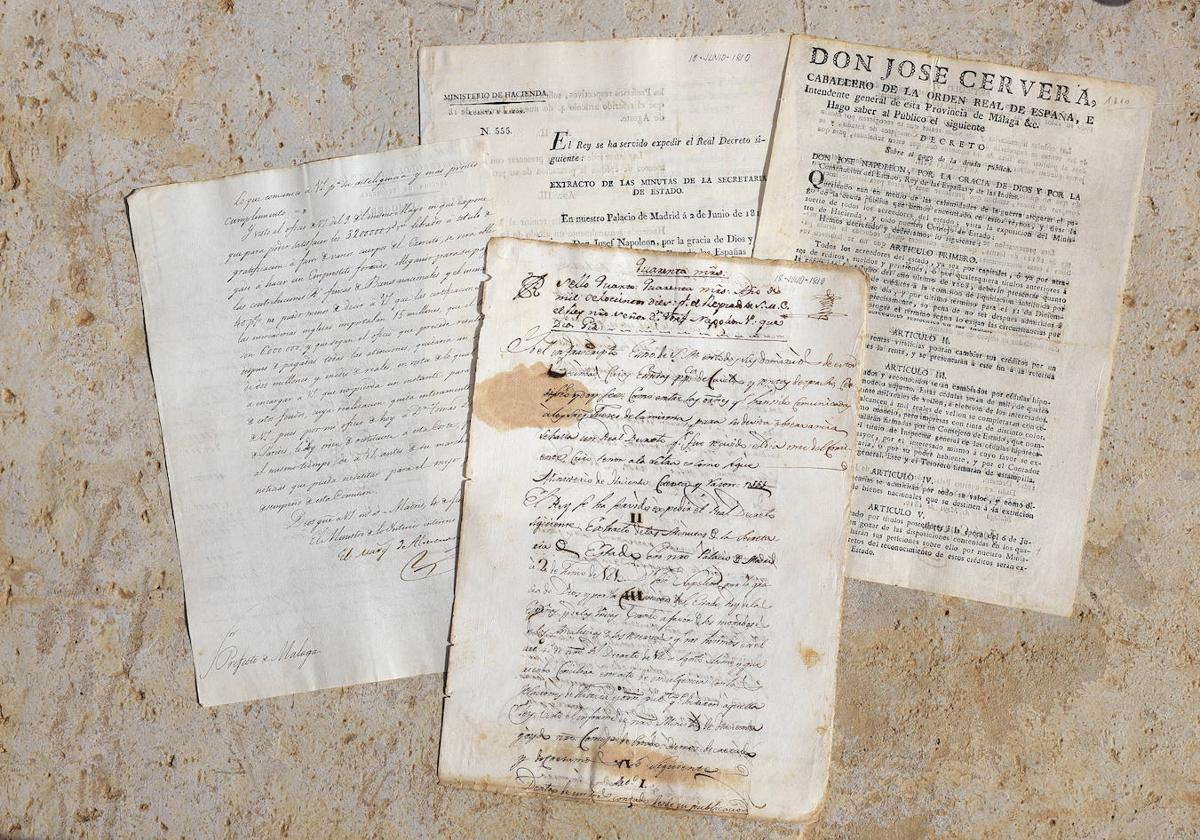

To his record of recovered pieces of history he now adds this collection of handwritten and printed documents in both Spanish and French that tell of the surrender of the city to “Joseph Napoleon, by the grace of God and the Constitution of the State, King of all the lands of Spain and the Indies”, as most of them state.

The papers have yellowed with age, but have lost none of their historical value. Particularly relevant is the letter written by the then General Sebastiani, the executor of the massacre of Malaga on the orders of Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult, Duke of Dalmatia and Bonaparte’s right-hand man.

Addressed to José Cervera, the Frenchified prefect (mayor) of Malaga appointed by the victors, the letter reminds the politician that he must pay the sum of twelve million reales for “the general expenses of the army” in the capture and control of the city, as well as requesting other sums, such as another 50,000 or 60,000 reales for the “headquarters” of Marbella.

Decree of King Joseph Napoleon

Co-signed by the Marquis of Almenara and minister Mariano Luis de Urquijo, this order issued in Madrid cancels previous taxes and imposes new ones. Ñito Salas

Decrees from the prefect of Malaga

In his search for funds to rebuild the city, the mayor José Cervera published these orders, in the name of King Joseph Napoleon, about the payment of public debt. Ñito Salas

Demands from the Treasury

The Marquis of Almenara also demands of the prefect of Malaga the “restitution” to the Crown of 2.5 million reales after an operation with “English merchandise”. Ñito Salas1 / 3

“What is striking is that the military man writes the letter in his own handwriting in French, which is unusual and gives a special value to the document and importance to what is requested,” says Fernández Molina, who has translated the letter which “is sent with cordiality and correctness, but which, despite being sent to one of ‘his own’, is written in a threatening tone so that the debt is paid as soon as possible and sent to Seville to the Duke of Dalmatia.” Indeed, in addition to the “distinguished considerations” that General Sebastiani uses in his dealings with the “prefect”, there is also a less friendly tone when he mentions that if the sums are not paid “I will be forced to use means of constraint”. A phrase which, spoken by the main perpetrator of the carnage committed during and after the invasion of Malaga, needed no further explanation.

The collection of documents acquired at the flea market includes several edicts printed and signed by mayor José Cervera himself, as well as by the minister of economy and finance and Marquis of Almenara, José Martínez de Hervás, who fled to France after the Spanish War of Independence.

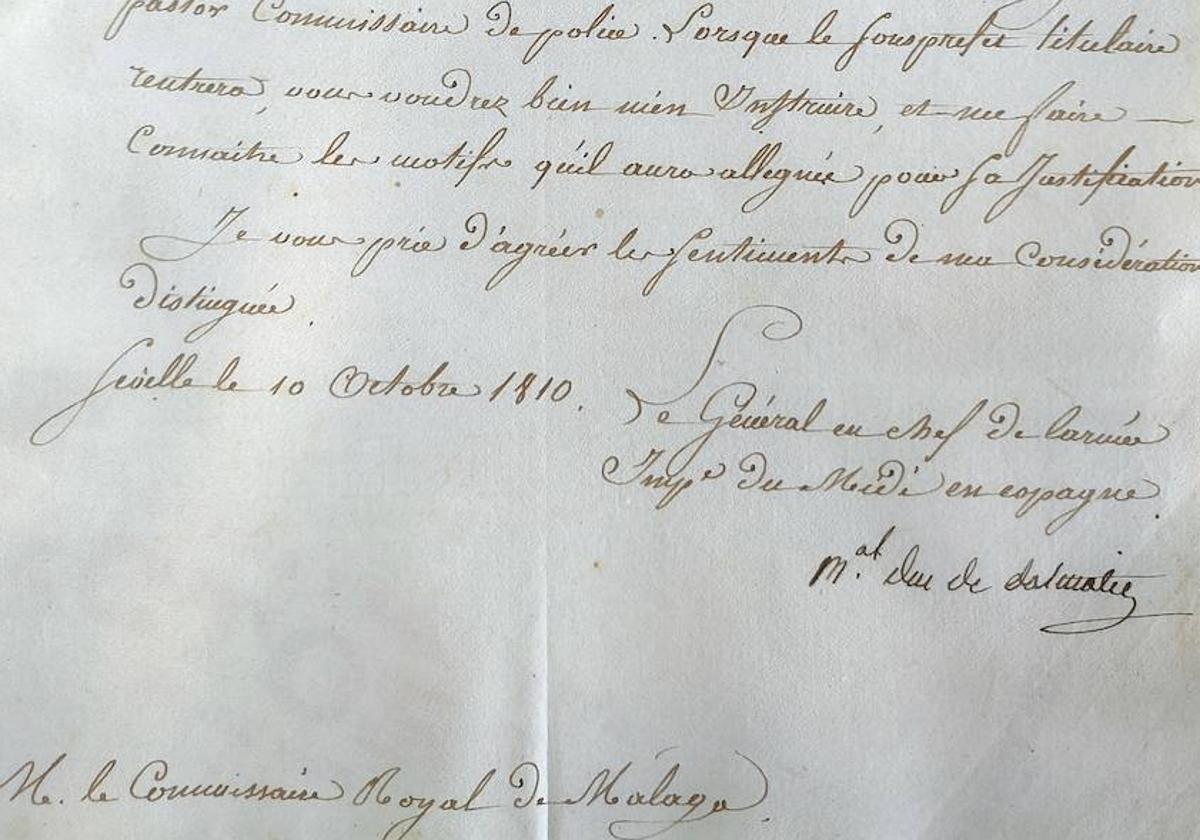

However, another missive that does not go unnoticed is the one bearing the signature of the Marshal General of France and Napoleon’s top leader of the invasion of Spain, Jean-de-Dieu Soult, who gives his noblest title, Duke of Dalmatia, at the bottom of his letter.

“What he does not say is that this hero of Austerlitz and Napoleon’s right-hand man was also the greatest plunderer of works and treasures from Spain, which in some cases were returned, but many were lost forever,” states Fernández, who points out the military man’s signature on the manuscript sent to Malaga in July 1810 from his headquarters in Seville. A missive that also gives a measure of the character’s harshness as it states that, after the prefect of Antequera presented himself in Seville to ask for a rest for health reasons, he was treated almost like a deserter and sent back to his post.

A secret woth keeping

It is specifically the presence of these documents signed by Soult and Sebastiani that gives a special value to the collection. Other documents that also stand out are the royal decrees and orders that, in the name of Joseph Bonaparte (popularly known as ‘Pepe Botella’), request money from Malaga time and again for support of the troops and payment of the city’s debts. Although in Spanish and French from a couple of centuries ago, the texts are readable.

“Because of their state of preservation, they have been in safekeeping and the person who sold them to me at the flea market knew they were worth money,” says Fernández. He outright refuses to reveal what it cost him to acquire these records, even off the record. “Their value is not what I paid for them,” is all he says.

Napoleon’s men in Spain use threats and harsh words in their writings to impose the new order

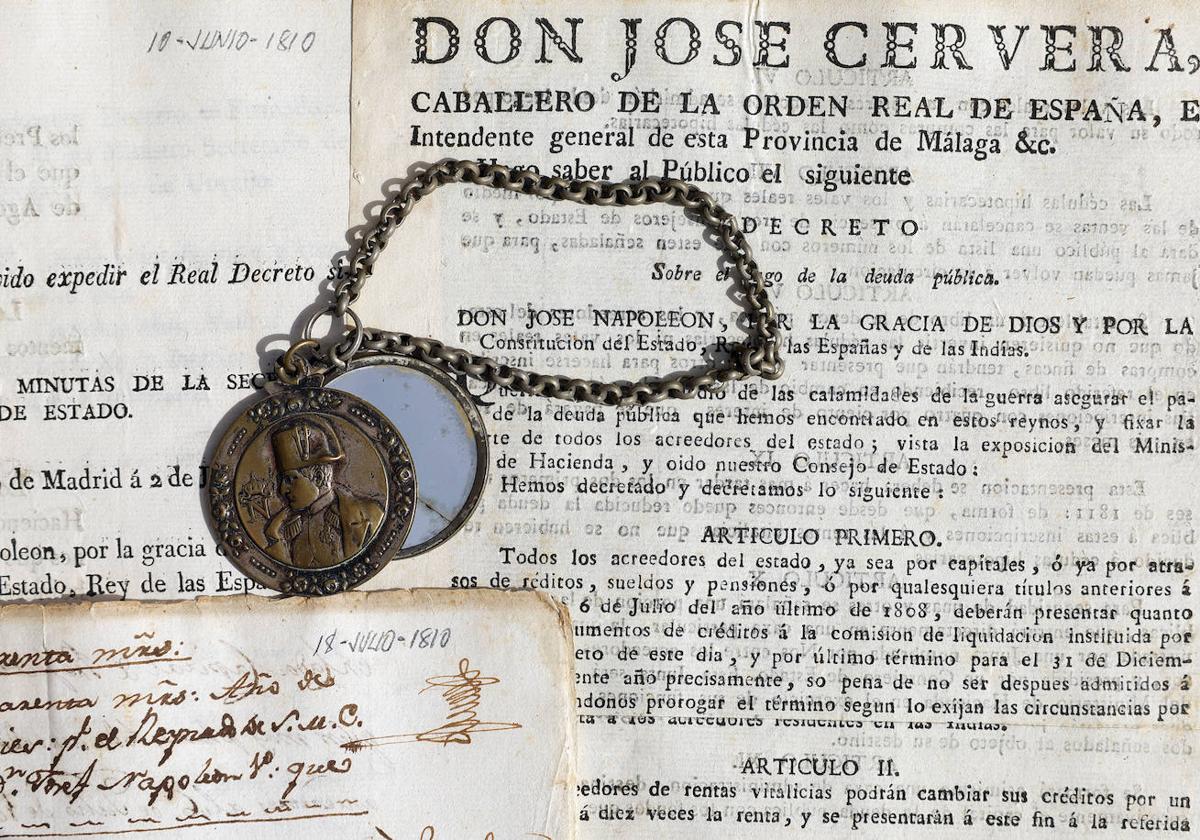

The job lot included not only papers, but also several souvenirs, such as a Napoleon medal that opens up to reveal a cute mirror inside for a quick touch-up and several medals, including one that is especially difficult to acquire.

“This decoration is the Legion of Honour, the highest French distinction established by Bonaparte himself in 1804.” Fernández Molina wears the face of victory, some 200 years after the battle that took place on the same stage where we are holding the interview, as he takes out this so distinctive award, whose gold centre reproduces an effigy topped with a laurel wreath and surrounded by the words: “Napoleon Emperor of the French.”

“The medal is valuable, but we cannot confirm that it belonged to any of the marshals in Spain or to any other personage, because we do not have the documents to prove it,” says the expert, who continues to study the details of the documents that he would like to exhibit in the city due to their importance.

“This case is special and has really struck a chord with me, because as a Malagueño this speaks of us, it is part of our past,” says Fernández, the latest local man to join the ranks of the resistance against French invaders from two centuries ago. A heroic and cruel story that comes back like a blast from the past, told in the handwriting of its own protagonists.

¿Tienes una suscripción? Inicia sesión

Comentar es una ventaja exclusiva para registrados

¿Ya eres registrado?

Inicia sesiónNecesitas ser suscriptor para poder votar.