Secciones

Servicios

Destacamos

Regina Sotorrio

Thursday, 6 April 2023

He died on the morning of 8 April. It took several hours for the news to reach the city. International agency United Press contacted the artist's cousin Manuel Blasco to get his reaction. Picasso, contrary to what some thought, was not immortal.

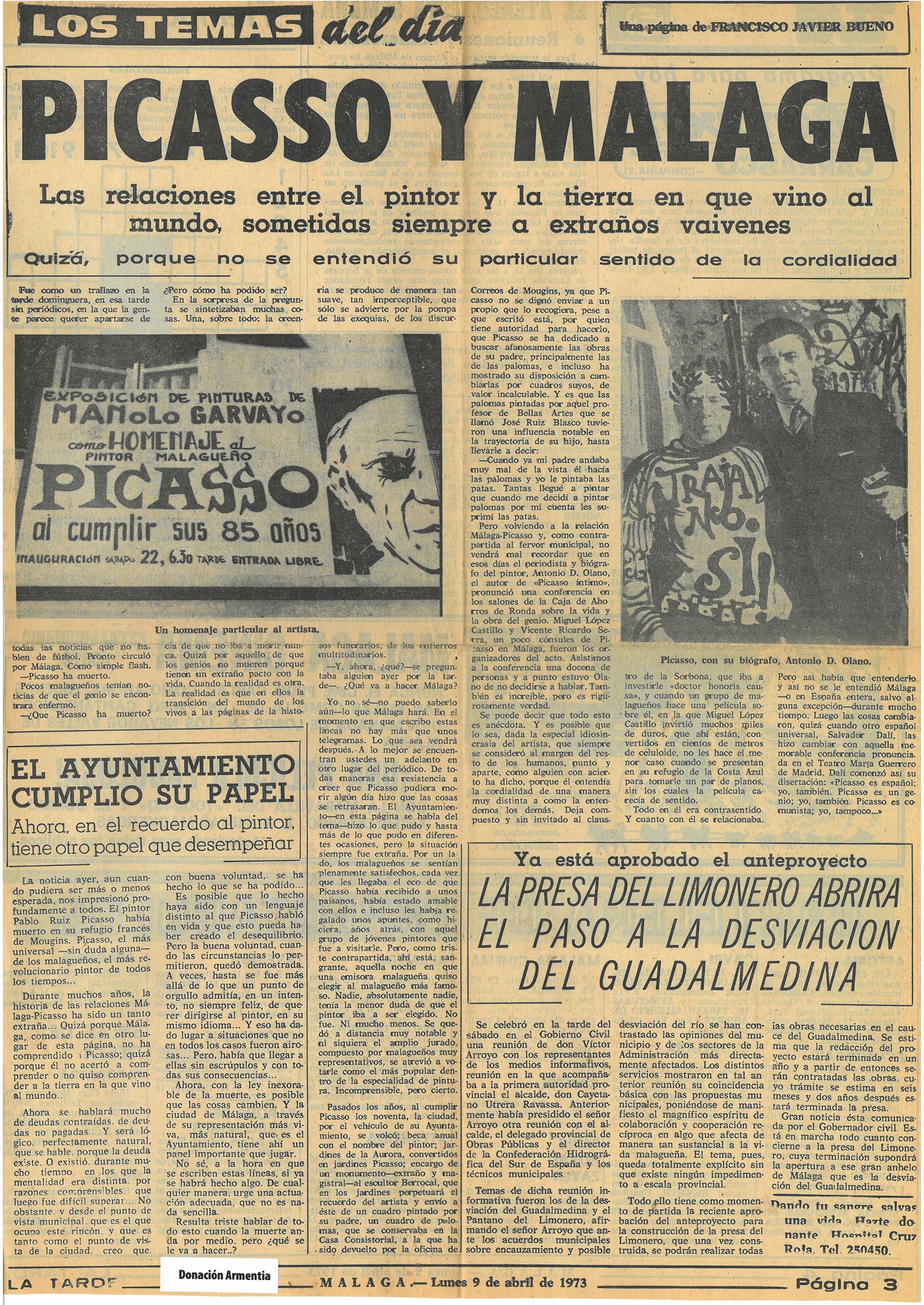

That day Picasso also died in the city of his birth, in Malaga, but here it was felt differently from in the rest of the world. While Barcelona and France mourned the genius, proud of their close relationship with him, in Malaga the grief was mixed with anger and frustration. The city had missed its chance to recover its natural connection with the most universal person to have been born here.

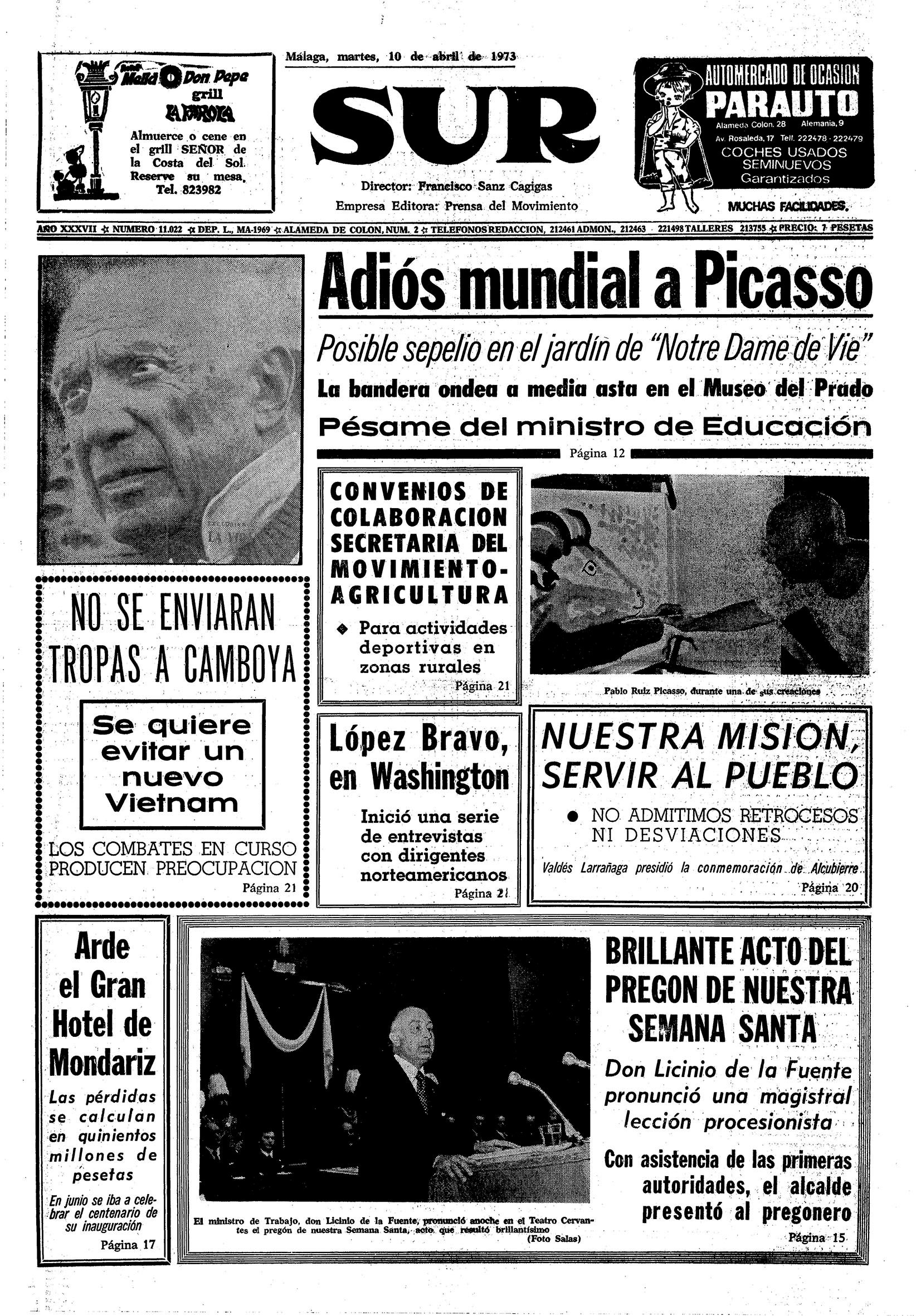

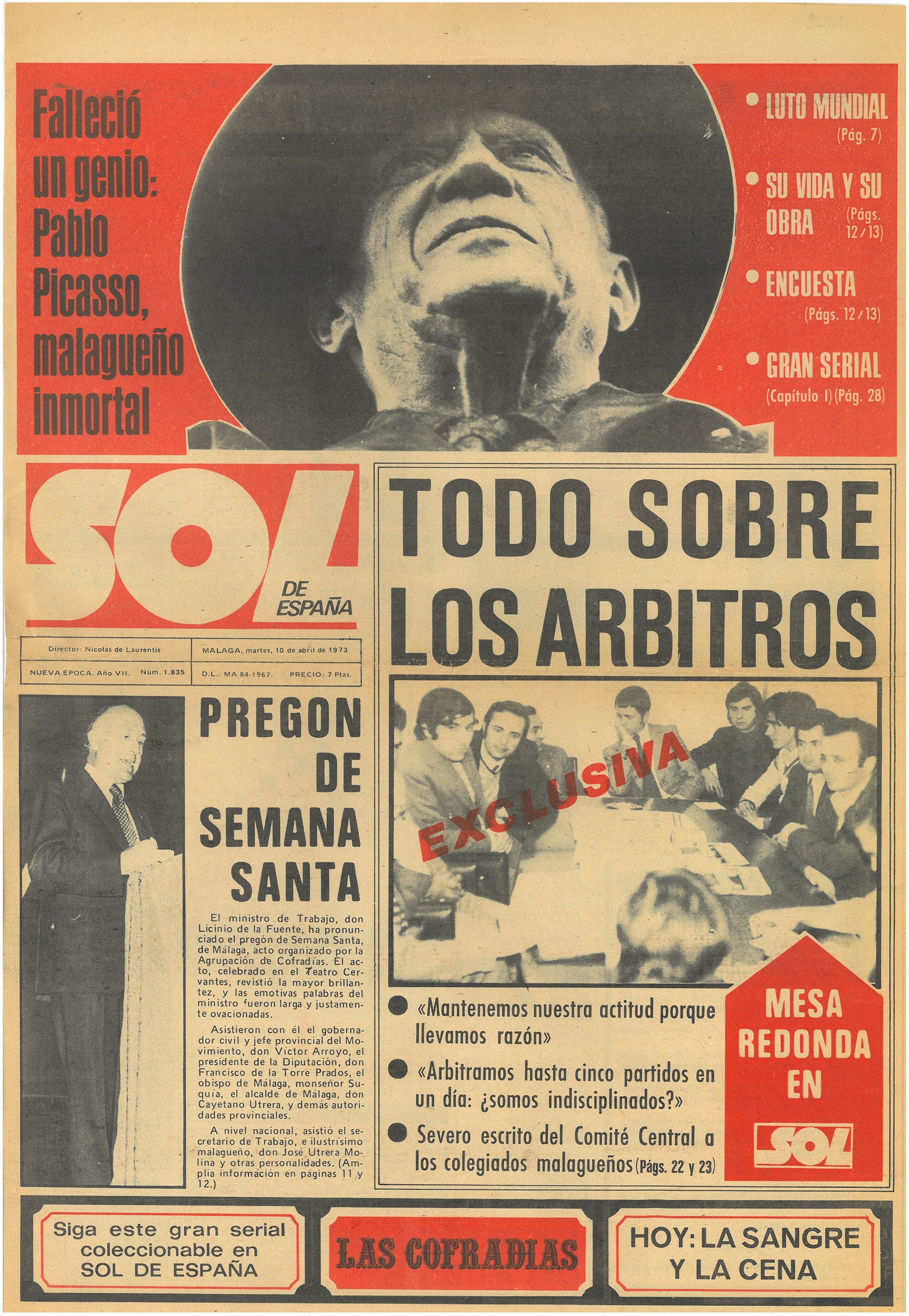

"Malaga will now break down barriers to approach the spirit of his genius, as death will open paths that sometimes life is incapable of opening," said a prophetic editorial published in SUR on Tuesday 10 April (there was no paper on Mondays).

It was the local people who reacted first to the painter's unexpected death, before any authority or institution: two anonymous gestures of great symbolic value caught the attention of the national press. According to the newspaper ABC, soon after the news arrived, a black ribbon appeared next to the "simple stone" on the building in Plaza de la Merced that indicated his birth place, which then was still private property.

And someone, still according to the newspaper, placed a bunch of roses "on the glass case that holds the greatest relic of the Malaga Fine Arts Museum", childhood sketches by the artist and a painting dedicated to the teacher who most influenced him, Antonio Muñoz Degrain.

These two small and moving gestures demonstrate the difference between Malaga and other parts of the world: Picasso was born and raised here, and that is the only thing that could not be taken away from the city. And practically the only link it had left to claim.

Context is required to fully understand the conflicting sentiments the painter's death produced in Malaga.

Four years previously, when Picasso's 90th birthday was approaching, in Malaga movements were stepped up to appeal to the childhood memories of the world-renowned artist.

Historian José Manuel Moreno Moreno lists some of the plans in his work 'La recuperación progresiva. Málaga a Picasso (1953-1973)' (Malaga's progressive recovery of Picasso). To sum up, in 1969 Galería Picasso was opened in Plaza del Teatro, the newly created Ateneo association dedicated its first events to him, the local culture magazine Litoral published a special edition and the Fine Arts Museum acquired one of his adolescent sketches. On the local cultural scene the idea that Malaga "needs to get Picasso back and soon" had been firmly established. Cultural institutions such as the Ateneo started to call for, among other things, a museum in Plaza de la Merced.

In 1971, coinciding with his 90th birthday, the city hall approved a number of initiatives geared towards paying off its debt with the most universal artist.

They set up the Becas Picasso, grants for local artists; a new park would be named Jardines Picasso with a monument to the painter; and the first steps were made towards buying the house of his birth for the city.

It was also established that the city hall would send Picasso a painting by his father, José Ruiz Blasco, The Dovecote, which is now on display in the birth place. This is one of the least known and perhaps most disconcerting episodes in the relationship between Malaga and Picasso. According to the newspaper La Tarde, the city hall sent the painting to Mougins, but it was returned to Malaga by the French post office "as Picasso didn't deign to go and pick it up", despite having searched for paintings by his father, especially those of pigeons, it said.

In SUR, the mayor Cayetano Utrera tried to smooth things over and didn't blame the artist, instead explaining that the city had sent the painting to his counterpart, the mayor of Mougins, and that he hadn't had the chance to hand it over.

Picasso did not react publicly to these signs being sent out in his direction from Malaga. It was too late. "What do I have there?" he said a few years before he died to his cousin Manuel Blasco when he encouraged him to visit Malaga after talking about it for hours at a reunion in France. And he was not wrong: there was nothing to tie him here. For more than 20 years Barcelona had been going to great lengths to nurture its relationship with him; and the Picasso Museum that opened in the 1960s was its reward.

The closest Picasso got to Malaga at that time - apart from personal contacts - was when his daughter Paloma visited the city in 1971, to see her father's homeland and receive a medal awarded by the Ateneo.

"Do you think your father will come to Malaga?" asked a SUR journalist. And she replied honestly. "I don't think so. Forty years ago he expressed his opinion about coming to Spain and it hasn't changed." She added, however, that her father "feels Spanish and 'Malagueño'".

"He didn't speak Castilian [Spanish]. He spoke and expressed himself in 'Malagueño'," Manuel Blasco had also said.

Two years after these desperate attempts to connect with the painter, and with practically all the promises still to keep, Picasso died.

After the initial headlines announcing the death of the city's "most illustrious son" came the analysis.

"Judging Picasso now for his split from Malaga would be to downplay us and downplay him. Focusing on how he treated the land where he was born would be to ignore the value of genius and fall into inadmissible chauvinism that would cloud good judgement. Malaga, Spain and France let Picasso go because of his universal spirit (...) We are sure that there was no lack of understanding between Malaga and Picasso. However there were two similar forces, arrogant and uncompromising, that clashed," said a SUR editorial.

As far as institutions were concerned it was Malaga University that first settled scores with the painter. That same 8 April, the rector Antonio Gallego Morell announced that the new university would have Picasso's "universal dove" in its coat of arms.

It was not a spontaneous tribute: the day after he took on the role he had already written to Picasso to tell him. "It's a shame that Pablo Picasso has not been able to hold in his hands the first letter sent from Malaga with the university's letterhead. And in that, the dove," he said in La Tarde.

That was just the start of decades of projects that posthumously reestablished Malaga's relationship with the painter, including opening the birthplace to the public and later the Picasso museum. Picasso may have died in France that day, but in Malaga he rose again.

Noticia Patrocinada

Publicidad

Óscar Beltrán de Otálora / Gonzalo de las Heras (graphics)

Encarni Hinojosa | Málaga

Jon Garay e Isabel Toledo

Esta funcionalidad es exclusiva para registrados.

Reporta un error en esta noticia

Debido a un error no hemos podido dar de alta tu suscripción.

Por favor, ponte en contacto con Atención al Cliente.

¡Bienvenido a SURINENGLISH!

Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente, pero ya tenías otra suscripción activa en SURINENGLISH.

Déjanos tus datos y nos pondremos en contacto contigo para analizar tu caso

¡Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente!

La compra se ha asociado al siguiente email

Comentar es una ventaja exclusiva para registrados

¿Ya eres registrado?

Inicia sesiónNecesitas ser suscriptor para poder votar.